Yet I choose to speak and die, rather than rot away in silence.

In 1934, during the Japanese colonial period,

a short essay was published in the magazine Samcheolli.

Its title was A Confession of Divorce.

The author was Na Hye-seok.

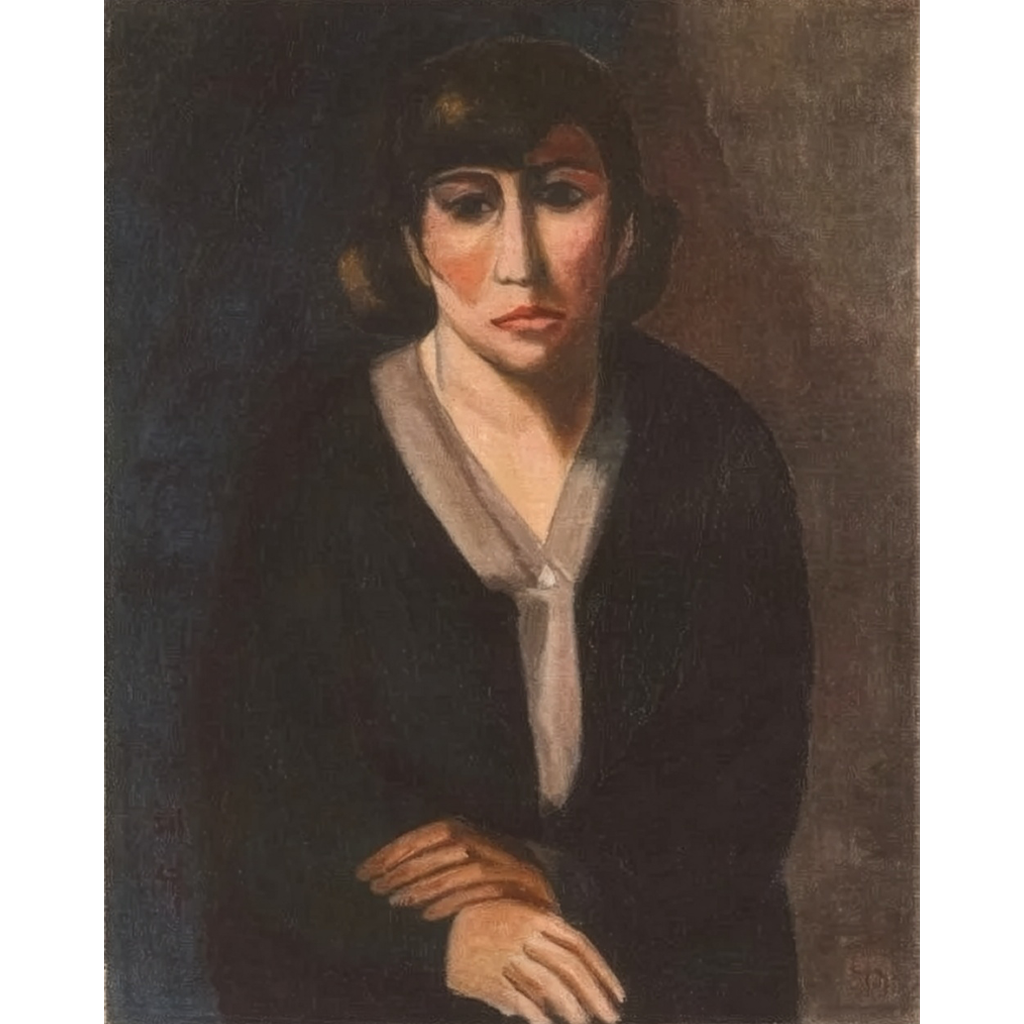

She was known as Korea’s first female Western-style painter and a “New Woman.”

After her divorce, she wrote this piece as a direct challenge to society

and to a male-centered social order,

laying bare her life and her emotions in public.

As I write this, I have no intention of making excuses.

I only wish to state the facts of what I have lived through, as they are.

The essay does not begin with self-defense.

It confronts marriage and divorce, chastity and desire,

and directly criticizes the sexual standards imposed only on women.

I believed marriage to be the completion of love.

But marriage, for me, became the grave of love.

I loved my husband,

yet married life slowly drove me toward death.

The society of that time was one in which

a male-centered patriarchal order oppressed women as a matter of course.

And in such a society, one woman asked a question.

Joseon society values a woman’s chastity more than her life.

But what is chastity, really?

If it is permitted to men but forbidden only to women,

then it is not morality—it is violence.

My husband demanded obedience from me.

I was a woman who thought,

a woman who spoke,

a woman who made art.

All of these became sins once I was a wife.

Na Hye-seok was born in 1896 in Suwon, Gyeonggi Province,

the fourth daughter of a relatively well-off family.

She rejected the conventional ideal of the “good wife and wise mother”

and made clear her determination to live as an artist and an intellectual.

She studied Western painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in Japan

and is recorded as Korea’s first female Western-style painter.

Her 1918 short story Gyeonghui depicts a female protagonist

who chooses her own life for herself.

It is regarded as the first full-fledged feminist short story

in Korean literary history.

She painted, she wrote,

and she sought to think through women’s lives on their own terms.

She also took part in the March 1st Independence Movement

and was imprisoned for it.

Her husband was Kim Woo-young.

The two met in intellectual circles of the time,

grew close quickly, and soon married.

Later, they left for France due to his overseas work.

Kim Woo-young was busy with diplomatic duties,

while Na Hye-seok devoted herself to studying art.

In that unfamiliar city, Na Hye-seok came into contact with Choe Rin,

another outsider like herself.

He was a well-known intellectual and one of the representatives

of the March 1st Movement.

Na Hye-seok, a New Woman, and Choe Rin, a charismatic intellectual—

it was the 1930s, often remembered as a romantic era.

But their encounter did not end like In the Mood for Love.

I did not intend to betray my husband.

But in a marriage without love,

how is a woman supposed to live?

Joseon morality says:

“A woman must endure.”

But I ask:

Why must a woman endure endlessly?

What is marriage?

How can a marriage that does not respect each other’s humanity

possibly endure?

I had an unhappy marriage.

And I did not hide that unhappiness.

If that is my crime,

then I acknowledge it.

Her husband, Kim Woo-young, learned of her relationship

and chose divorce.

The official reason given was adultery.

Na Hye-seok was already a public figure.

Her fame was instantly transformed into scandal.

The public reaction was so cruel that,

even by today’s standards of celebrity scandal, it would not seem excessive.

No time for recovery was granted.

“Debauched.”

“Immoral.”

“The downfall of a New Woman.”

Newspapers and magazines portrayed Na Hye-seok

as the cause of a broken family.

“She betrayed her husband” came first,

followed closely by the sneer, “New Woman.”

No one asked

what her marriage had been like,

what had collapsed within it,

or why it had ended in divorce.

Because no one asked, she had no chance to answer.

That void was filled with condemnation.

During all this, Choe Rin never once spoke in her defense.

There was no explanation, no clarification.

Na Hye-seok had to endure all those stares alone.

And then she decided to remain silent no longer.

I divorced.

For one reason only:

to live as a human being.

Marriage is entered into without any trial.

But how can something that determines an entire life

be decided without any test at all?

I believe that living together before marriage should be allowed.

If it can prevent greater unhappiness,

what, then, is immoral about it?

Because of these words,

I will be buried by Joseon society.

Yet I choose to speak and die,

rather than rot away in silence.

A Confession of Divorce entered the world that way.

Her husband left, her lover turned away,

society condemned her, and she was effectively buried alive.

Not a single painting sold.

No publication would carry her writing.

There was no one left at her side.

In 1948, Na Hye-seok died at the age of fifty-two.

Because she died alone,

even the location of her grave is unknown.

I am not ashamed of my life.

What should be ashamed

is a society that silences women.

To those who read this,

you may curse me if you wish.

But at least once, think about this:

why women were expected to endure endlessly.

Her cry from 1934

reaches out and grips me in 2025.

Her adultery was wrong even by today’s standards,

and it was undeniably grounds for divorce.

That fact is not denied.

But this text goes beyond the issue of adultery.

It draws a tragic portrait

of a single human being crushed by her time.

She loved,

was abandoned because of it,

was ruined because of it,

and died alone.

Her life is unbearably painful to contemplate.

Who would not wish

to meet someone they love

and live quietly and happily forever?

But fate never leaves us alone.

Having been utterly abandoned

and turned away from by everyone,

what she chose in the end

was still to speak.

Even if no one listened,

even if no one stood on her side,

she spoke.

Her paintings,

her words,

are still alive.

As I bring this final essay of 2025 to a close,

I want to end it by remembering one name:

Na Hye-seok.

—

By Sunjae Park

Editor, Korea Insight Weekly